Elements of a Contemplative Reformation, Essay #4

“Conscious and Incarnated”

The Rev. Dr. Stuart Higginbotham

This essay is the fourth in a series of essays on the Elements of a Contemplative Reformation. For a while, we have been reflecting on this possibility at Grace Episcopal Church, exploring the richness of the contemplative tradition through various lenses within our common life.

The first essay was “A Call to a Contemplative Reformation” and can be found here: https://contemplativereformation.wordpress.com/2017/09/15/a-call-to-a-contemplative-reformation-the-essay/

The second essay was “A Tale of Two Postures: Grasping and Self-Emptying” and can be found here: https://contemplativereformation.wordpress.com/2017/12/11/a-contemplative-reformation-essay-2-a-tale-of-two-postures-greed-and-self-emptying/

The third essay was “Listening for Withness: Engaging Silence in a Multi-ethnic and Multi-racial Reality” and can be found here: https://contemplativereformation.wordpress.com/2018/05/11/elements-of-a-contemplative-reformation-essay-3-listening-for-withness-engaging-silence-in-a-multi-ethnic-and-multi-racial-reality/

This essay continues this theme of exploring a particular facet or dynamic of parish ministry.

The other day, a member of my parish asked me if I had read Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” I told her that I had, of course, read this letter several times in various seminary classes. It was and continues to be a pivotal reflection on Dr. King’s understanding of the necessity of the protests in Birmingham during the crucial years of the Civil Rights Campaign. The story of the Letter itself is legendary: written on pieces of paper, taken out in sections, compiled by the team, and then mailed out to several ministers in the Birmingham area. Many view the publication and distribution of this letter as a watershed moment in the Civil Rights Movement, a blooming and expansion of consciousness of the plight of African-American persons within their own country.

We remember that Dr. King wrote the letter to ministers in various churches, because there was a lack of awareness of why the protests and broader Civil Rights Movement was necessary. People were upset at the disturbance the protests were causing in society, and Dr. King felt compelled to address this resistance head on:

You deplore the demonstrations that are presently taking place in Birmingham. But I am sorry that your statement did not express a similar concern for the conditions that brought the demonstrations into being. I am sure that each of you would want to go beyond the superficial social analyst who looks merely at effects, and does not grapple with underlying causes. I would not hesitate to say that it is unfortunate that so-called demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham at this time, but I would say in more emphatic terms that it is even more unfortunate that the white power structure of this city left the Negro community with no other alternative.[1]

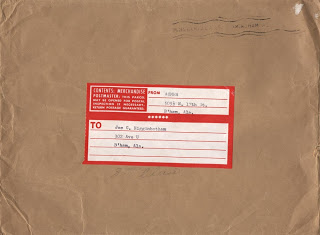

When I sat down in my study to explore this document again, I was surprised to see an image I had never noticed before. It was an address label from one of the original postal packets.

There, listed on an address label was Joe C. Higginbotham, who I learned was a Methodist minister there in Birmingham who received one of the original letters from Dr. King. Apparently, his son, Dr. John C. Higginbotham, associate dean for research and health policy at the University of Alabama’s College of Community Health Services, found the letter while cleaning out his father’s papers after his death in December 2005. The Higginbotham family since donated the original letter to the University of Alabama in celebration of this crucial experience—and vital lesson—in American life and culture.

I have been transfixed by this parcel. It feels like I have a stronger resonance with the Letter than I did before. Now, there is a part of its story that connects with my story. A Higginbotham, who was a minister, received one of Dr. King’s Letters from a Birmingham Jail. Perhaps one day I will have the opportunity to visit with his family and hear their story. Perhaps we will discover we are third cousins. Such is the power of stories, as we know.

To me, the story of the Letter is one of deep yearning, of a prayer that those in positions of power and privilege may be awakened to the plight of those in positions of oppression and burden. Dr. King is not necessarily saying that anyone or everyone to whom to the Letter is addressed is actively participating in the oppression and violence toward minorities; however, he is making clear that all are called to a heightened degree of consciousness. Consciousness is essential, as is the responsibility and the transformed embodiment that flows from heightened consciousness. To be sure, this tension around consciousness and our call for a transformed embodiment continues to be a struggle for the institutional church. Perhaps it always will be.

These past several days, I have been intrigued at some of the responses to Bishop Michael Curry’s sermon at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle. While the vast majority of folks in my sphere have shared their outright glee at both the message and the opportunity to share it, others have scrunched their eyebrows and shared opinions that all orbit around a common theme: there was something undignified about the entire sermon that made them uncomfortable. There was something uncouth afoot.

What is it about this seemingly improbable opportunity for global evangelism that makes us squirm a bit? On the level of “good press,” who could ask for more? On the level of sharing the Good News of Jesus, who could imagine a more gracious opportunity for bringing hope in a world so plagued by fear and anxiety. For the folks who were scrunched, were they more disturbed by the way Bishop Curry said what he said, or are they honestly uncomfortable with what he said? I wonder.

As a parish priest who is also sharing in global conversations about the ongoing development of the broader contemplative lineage within the Christian tradition, I am constantly intrigued by the resistance within institutional churches to experiences or opportunities that seem threatening to the status quo. How many times have we heard the response, “We’ve always done it that way.” When I think on my own experiences at Grace Episcopal Church—in our ongoing conversations around being a contemplatively grounded community, that is, one that is centered or rooted in an awareness of our union with God and our responsibility to embody compassion from such a transformed consciousness—I am vividly aware of the pressures of institutional maintenance.

As I was reflecting on this article, I remembered a video interview of Bro. David Steindl Rast, a Benedictine monk, and Fr. Thomas Keating, a Cistercian monk, as they reflected on the role, importance, and function of the traditional institutional church. In the video, entitled “What Good is the Church?” these two pivotal spiritual teachers share an honest understanding of both the limits and the hope found within the institutional Church. I invite you to take a few minutes and watch this video.[2]

At one point in the video, Fr. Thomas shares that “the established doesn’t care to be disestablished.” He describes his encounter with Pope St. John XXIII, a figure who he believes was rare in the simultaneous embodiment of both institutional maintenance and prophetic or contemplative vision. I appreciate their honesty in naming the need for the institution to carry the tradition, to ensure the continuity of the teaching of the Church throughout time. To me, this is an essential function of the institution as such. That being said, we must also realize the need for the prophetic or the contemplative to challenge any hyper focus on the maintenance of the institution. At this point, I hear Dr. King’s plea echoing through the decades:

You deplore the demonstrations that are presently taking place in Birmingham. But I am sorry that your statement did not express a similar concern for the conditions that brought the demonstrations into being.

Such a reflection challenges me to consider all the ways I err on the side of institutional maintenance when faced with a call for prophetic action—of risk. And, perhaps, there is the word we need to say aloud: risk. How am I willing to risk as the rector of Grace Episcopal Church? What is mine to risk? How should I listen to the heart of the community when considering such a risk?

Perhaps this connects with your own experience in preaching. Lord knows that is an area that feels more risky by the week given the political pressures and anxieties swirling around us like darkened birds of prey. I recently took a risk in a sermon and criticized the criticizers who have told me I have been “too political.” “As if Jesus ever shied away from naming what needed to be named in circumstances of societal injustice and oppression,” I told them. A few thanked me for being honest. Only a few. And, such a sermon is all well and good in mid-May, but will I be as willing to take a risk come September when Stewardship Season is starting? How do I balance all of this? Should I even be concerned with balancing it?

I also recently took a chance to send out a pastoral letter to my community, including a link to the recent statement by several prominent Christian leaders, including the Rev. Dr. Walter Bruggemann, Fr. Richard Rohr, and Bishop Michael Curry, among others. The statement is bold—and necessary, I would add. It speaks of the heresy of any “American First” platform and it calls to question our growing and shocking willingness to accept lies from our political leaders. I received a few responses from folks questioning this “Reclaiming Jesus” statement. A couple folks in particular maintained that we are a nation of laws, and that all our laws must be maintained. This maintenance of the laws, they claimed, was what made us strong as a country.

Does this suffice? I asked my wife when I got home that night if anyone would have made that comment just prior to the 13th Amendment being passed, or the 14th, 15th, or 19th, for that matter. What would I have said just prior to those moments in American history when it seemed like the foundation of our laws was about to be changed—or broken, depending on where one “stood” on any issue. Is maintaining the institution the key? Or is there something more? Must there be something more? Put another way, how do we understand the Spirit’s urge, push, nudge, enticement to grow and develop, to expand rather than restrict, to embrace rather than reject, to seek hope rather than persist in fear and scarcity?

I think back to an article I read many years ago by Bro. David Steindl Rast. Martin Smith shared it with us at a clergy retreat, and it has stuck with me since then. In “The Mystical Core of Organized Religion,” Bro. David describes the essential framework at the heart of organized religion’s development over time.[3] There is, he argues, a “Founder’s Mysticism” at the heart of every religion’s establishment moment. In that space, there is a first-hand experience of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. Over time, the mind refracts these experiences, and institutions are formed to maintain the original experience itself—although that is, in a profound sense, impossible to do. With the addition of historical influences in the procession of time, what was this firsthand experience of profound Truth, Goodness, and Beauty becomes institutionalized as Dogmatism, Legalism, and Ritualism. The urge to preserve becomes pronounced, and the essence of the mystical heart of the religion seems quite distant.

Such is the pressure of the institution itself and thus we experience the urge to maintain. Such is the procession itself that, over time, the maintenance of the religious framework becomes the way we feel we are being most authentically religious! This is what is behind the ubiquitous statement, “We have always done it that way.” This, I think, is what we would find should anyone be brave enough to dig behind their perceptions of uncouth royal sermons.

But we are a religion that believes in the life-giving and rock-shattering power of the Spirit, so we should expect some tension at some point. We must never be satisfied with the mere maintenance of the institution itself. As Bro. David and Fr. Thomas say in their video above, the institution is the carrier of the tradition; thus, it is the means to the end—not the end in itself.

In his essay, Bro. David draws on the image of a volcanic eruption to imagine the process of institutionalization. With the immediate experience, the fire and lava poured forth. “There was fire, there was heat, there was light: the light of mystical insight freshly spilled out in a new teaching,” he says.[4] Over time, the post-eruption environment saw the lava cool into rock. “Dogmatism, moralism, ritualism: all are layers of ash deposits and volcanic rock that separate us from the fiery magma deep down below.”[5] Even with the inevitable cooling that happens, the fire of the Spirit continues to swell.

But there are fissures and clefts in the igneous rock of the old lava flows; there are hot springs, fumaroles, and geysers; there are even occasional earthquakes and minor eruptions. These represent the great men and women who reformed and renewed religious tradition from within. In one way or another, this is our task, too. Every religion has a mystical core. The challenge is to find access to it and to live in its power. In this sense, every generation of believers is challenged anew to make its religion truly religious.[6]

In the end, such is our shared call, is it not? As religious communities we are called to a shared reality of consciousness and incarnation: to be aware of the call of Christ on our lives (and our deafness and resistance to it) and our shared mission to incarnate the Good News of Christ in the world around us (and our hesitancy to yield our egoic grasping nature). I think this is what Dr. King was saying to those pastors, including dear Rev. Higginbotham. I think it is also what Bishop Curry and so many others are trying to say now. As people who dare to call themselves followers of Jesus, we are called to be people who contemplate the love of God that breaks the rocky soil of our lives and lays bare our urge to protect ourselves in dogmatism, legalism, and ritualism.

In our own age of anxiety and fear, Bro. David’s words offer us hope:

One of the great surprises is that the fire of mysticism can melt even the rigor mortis of dogmatism, legalism, and ritualism. By the glance or touch of those whose hearts are burning, doctrine, ethics, and ritual come aglow with the truth, goodness, and beauty of the original fire.[7]

[1] Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.” http://okra.stanford.edu/transcription/document_images/undecided/630416-019.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2018.

[2] https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=david+steindl+rast+mystical+core+of+the+world%27s+religions&&view=detail&mid=CCAE256DFE410342C451CCAE256DFE410342C451&&FORM=VRDGAR. Accessed May 29, 2018.

[3] David Steindl-Rast, “The Mystical Core of Organized Religion” as reprinted in the Council on Spiritual Practices. http://csp.org/experience/docs/steindl-mystical.html. Accessed May 29, 2018.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

Leave a comment