In Him All Things Hold Together

The Feast of the Baptism of Our Lord 2024

Stuart Higginbotham

This particular Sunday, the Feast of the Baptism of Our Lord, will always be a “red letter day” for me, here with you at Grace. This week begins my eleventh year with you, which is hard to believe. I look back on our decade together, and my heart is full when I see how the Spirit has been at work. My heart is also full of gratitude for the many ways you have helped make me not only a better priest but a better human being–although I know there is ample room for improvement.

This particular Feast of the Baptism of Our Lord is a fascinating one. We always observe it on the Sunday following the Feast of the Epiphany, which is, you could say, the final marker in the Christmas or Incarnation narrative. Epiphany marks the arrival of the magi to the Holy Family, and this Epiphany time is an ancient one, marking the manifestation of Jesus’ full humanity and divinity.

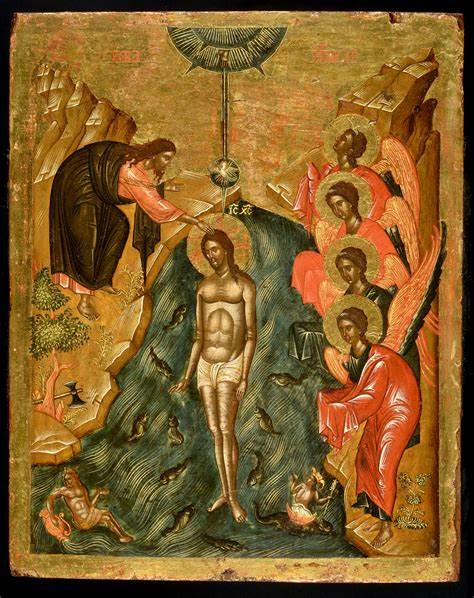

The text for today may be very familiar to us–although it can get overlooked a bit in the immediate post-Christmas exhalation. We know the outlines of the story: John the Baptizer is there at the River Jordan baptizing people. Jesus walks up to them and asks John to baptize him. John and Jesus have an exchange as to why this is necessary (depending on the particular Gospel interpretation). John baptizes Jesus, and the sky (in some form) opens up and the Spirit descends upon Jesus with a voice that recognizes him as God’s beloved Son.

While that is the basic outline, I would argue that this Gospel story warrants us pausing a bit today to look more closely. The Gospel account from Mark–this being Year B in our three-year liturgical cycle–begins with this line: “John the baptizer appeared in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.”

That was the reason John was doing his baptisms–which, we remember, were an interpretation of longstanding Jewish practices of ritual baths for purification. Here’s the question hidden in plain sight: If John was baptizing people with this ritual bath for purification and the forgiveness of sins, why was Jesus baptized? Think about that for just a moment and see what comes to you.

Why was Jesus baptized?

As we understand Jesus–who we understand Jesus to be in terms of the tradition of the church–why would Jesus have shared in such a ritual act whose purpose was to symbolize, embody, effect the purification of sins? This is a hinge question, so to speak, because an enormous amount of our practice of faith turns on how we understand the spiritual significance of this moment.

In terms of the mystical experience or awareness of Jesus, we see how God entered so fully into creation that no part of human existence was outside the bounds of God’s embrace. God took all of our life, the full spectrum of our human experience, into God’s own Self in the person of Jesus, the Incarnate Word of God.

So, in a powerful way, we see in today’s Gospel reading that it is not that Jesus just shares in the baptism that John was offering as though Jesus needed to be purified; rather, by participating in that ritual act, Jesus actually takes the entire symbolic and ritualistic participation of the act into Himself to transform it through his own life. This is the key understanding.

Notice that it starts off in the typical pattern of John baptizing Jesus, but it is then expanded with this mystical experience of the heavens opening and the Spirit’s presence being felt. There is participation and there is expansion here, what we could even call a transmutation.

The writer of the Letter to the Colossians picks up on this image of Jesus taking all aspects of our life into his own being in this way:

15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; 16for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. 17He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. (Colossians 1)

In this way, today, with Joshua’s baptism today, we experience this reality again: that all things hold together in Christ, who entered fully into all things and transforms them through His own being. We share in this reality as the writer of the Letter to the Ephesians describes 13until all of us come to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ. (Ephesians 4).

This is the essence of what it means to practice Christianity: that we become aware of God’s presence in all of life, through the embodiment of Christ’s life, within our life–which is all one life. And, in this awareness, our hearts are transformed and we live more consciously in the world, growing into the fullness of the stature of Christ as the Spirit guides us into wholeness.

Perhaps here is where we are challenged in our day and time: if all things hold together in Christ, if Christ takes all things into Himself and transforms them, then there is no aspect of our lives, no part, whether personal or collective, that is outside that circle of presence. Our faith is not something over here while other parts of our lives are, somehow, over there.

We sometimes hear people say “my faith is a personal thing,” and we see how we do a sort of gymnastics to keep our “personal faith” over here and our political, social, or civil life and beliefs over here. But this is a false dichotomy–actually a heresy–given the reality we know to be true: that Christ enters into every aspect of our life to transform it, and that we are transformed together as a community, as the Body of Christ.

Yes, we practice our faith in our personal lives, yes we say our personal prayers, and yes we are called to be accountable for the way we live our lives, but our faith is communal because our lives are shared. It is why we have a Book of Common Prayer, and our liturgy today reminds us that “there is one Body and one Spirit. There is one hope in God’s call to us. One Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all.”

So,we have to be very careful that we don’t take our Western, American ideals of individualistic success and think that is what the Gospel holds to be true–because it is not. Jesus called people into community, and every healing act he did transformed the lives of families, towns, empires, and the entire world. Our cultural assumptions around competition and greed and individual success are convicted, challenged, by the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

This is why we only do private baptisms in somewhat of emergency situations, because we share in this embodied, sacramental act as a community. This is why we don’t overly emphasize the notion of personal salvation that we see in some schools of Christian interpretation, because Jesus was utterly focused on forming communities–even to the extent of sharing his own Body and Blood with a gathered group of people who would then went out into the world to nurture other communities of faith. We are the Body of Christ together, and as the Prologue to John’s Gospel reminds us, the light that came into the world saturates all people and all creation. Nothing is outside of that light.

We live in a time when it is easy to think that all that matters is “my personal salvation.” If that is the case, no one else matters so why should I invest in them–except to convert them to my way of thinking. We have to be very careful about the effect this has on how we treat one another and how we live within creation. As Rabbi Abraham Heschel once wrote, “Any god who is mine but not yours, any god concerned with me but not you, is an idol.” Our culture is full of idols these days, and we see the harmful and sinful effects of equating such a fixation on personal salvation with political power that then leads us to think that we are the only chosen people in this world.

We also live in a time where we need to name out loud that, rather than affirming that all is held in Christ’s own life, that all is brought together and transformed in Christ’s own life, that it is Christ’s life which shapes the way we live in the world, rather than focusing our hearts there, we so easily let our practice of faith be subsumed into the values of our Western American consumer culture.

A good test case is this: who was told as a child that “God helps those who help themselves?” That comes from Benjamin Franklin, not the Gospel. A major challenge we face is how do we challenge our culture’s obsessive individualistic focus on personal success and ambition with Jesus’ actual teaching to lay down our lives for our friends and love our enemies? There is an age-old tension between Christ and culture, as many have noted, and these are days that we must pay very close attention to what we believe and why we believe it–and how we are resistant to even reflecting on what we believe, which tells us something about ourselves.

Friends, we are stepping into a year that will be tumultuous. That is the polite word for what we fear this will be. There will be a lot of anxiety and anger, there will be a great deal of manipulating fears, and we should name this out loud and prepare our hearts to ask how we live faithfully in these trying times. We cannot compartmentalize our faith, and we cannot simply think that “coming to church” is only about comforting ourselves when we are convicted with how much in our lives needs to be transformed. These are not easy days, but I am totally convinced that we have the ability to face these challenges–because the Spirit is very much at work.

And that’s the key, isn’t it? That’s the deep truth of how we step forward with faith, hope, and love: that we trust the Spirit’s transforming power. We do not put our faith only in our own capacity or cleverness. We resist those who set up idols either in ideas or in themselves. We put our faith in the Spirit of the Living Christ whose presence fills our lives and reminds us how we are all united.

In this way, we stand alongside John, there at the Jordan River, watching for Jesus to come. We keep our eyes open, and we tell all those we know that there is one coming to whom we give our lives. And to this One, this Christ, we open our hearts and trust that our lives will be made whole, that love will cast out fear, and, as St. Julian of Norwich said “all will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

May it be so.

Leave a comment