Stuart Higginbotham

Sermon for October 22, 2023

Isaiah 45:1-7; Matthew 22:15-22

I would like to begin this morning with a poem I wrote this weekend, inspired by today’s reading from the Prophet Isaiah.

Treasures of Darkness (Isaiah 45:1-7)

Whatever the soul is, it is thirsty.

It craves water,

the hidden rivers within the earth,

calling to it, an unseen path to life.

We exhaust ourselves into hope,

breaking our bones on walls we build.

Our tired fingers finally fail and

let slip the dead weight of our stark ambition,

a dry husk lying at our feet,

the imprint of our own face,

as we stand bare to the sky.

You never seem to yell,

and perhaps that is part of the struggle,

because we only seem to listen to screaming,

those voices shrill and shouting,

trying to convince themselves of their importance,

trying to convince us to follow them,

while you sit silently, praying for us to have fresh eyes.

Yes, you pray,

and you will use what you will use,

taking us by the hand,

leading us all into new life.

We walk through our houses at midnight,

lighting every candle we can find

to push the shadows back,

because the truth they whisper

we cannot bear to hear:

that there is a God

that my image of God is

as brittle as blown glass

that the crack in the glass

is the doorway to freedom

that the price of true freedom

is the attachment to myself

that we will die

that we will live.

If I truly want to pray

I would do better with a shovel than a trumpet.

In the silence of the night I carefully dig

into the soft earth and gently uncover

the treasures of darkness.

I hold them reverently in my hands,

slowly running my fingers over the smoothness

of what life can be.

Today’s reading from Isaiah is powerful and very challenging. We remember that the Babylonians conquered Judea and took the leadership, at least, of the Jewish people into exile. The fall of the temple was a crushing moment for the Jewish people, and they were challenged to reorient their entire spiritual understanding because of it. As Psalm 137 says, “How can I sing a song in a strange land?”

But no empire lasts forever, and this is an inconvenient truth for those who believe they are invincible. The Babylonians themselves were conquered by the great Persian King Cyrus. Cyrus decided not only to free the Jews in exile, allowing them to return to their homeland, he also funded the rebuilding of the great temple in Jerusalem.

This brief review brings us to today’s reading, which is an exercise in spiritual imagination from the prophet Isaiah.

Thus says the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus,

whose right hand I have grasped.

The word used here in Hebrew for “anointed” is māšîaḥ mashiah. Now, if this word reminds you of another word, messiah, that would make sense because it is the same word. Isaiah recognizes Cyrus the Great, the ruler of Persia, as God’s Anointed, as messiah. Let’s reflect on this a bit.

Isaiah envisions God choosing Cyrus, working through Cyrus, for the healing and wholeness of God’s people.

I will break in pieces the doors of bronze

and cut through the bars of iron,

I will give you the treasures of darkness

and riches hidden in secret places,

so that you may know that it is I, the Lord,

the God of Israel, who calls you by your name.

Through Isaiah’s spiritual imagination, God is empowering Cyrus to bring about the restoration of the exiled Jews. This is God’s doing, God’s choice, and Isaiah describes God Godself speaking to Cyrus and saying:

I call you by your name, I surname you, though you do not know me.

I am the Lord, and there is no other;

besides me there is no god.

I arm you, though you do not know me,

God chooses Cyrus, the Persian king, and Isaiah envisions God working through him, although, as the text says, Cyrus does not know God.

This passage is an example of prophetic imagination that breaks through every assumption we may have about a quid pro quo when it comes to God’s blessing, as in “if I do this, then God will bless me,” etc. No, here is God working through someone totally outside in order to bring about the healing God desires–independent of them doing anything in return or even necessarily recognizing God’s movement.

The lesson here is that God will use whom God will use. Full stop.

Now, we can read today’s Gospel alongside this text from Isaiah to discern Jesus’ own perspective some five centuries later. The Pharisees are plotting to catch Jesus in some tangled understanding of loyalty. At this point, the Jewish people are under Roman rule, of course, so they ask if it is lawful to pay taxes to the emperor. Jesus asks for a denarius and then asks them, “whose head is this, and whose title?” Since it was Caesar’s, Jesus tells them, “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And the text says they were amazed.

What do we learn here? We learn that Jesus, as the Incarnate Word of God, will not be bound by categories such as the ones they try to impose. Jesus points them, and us, outward, beyond the frameworks of empire and such. Jesus’ statement “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s,” of course begs the question “what things are God’s?”

God will use whom God will use to bring about the healing God desires for the world. God is not bound by our understanding of society, nationality, or religious beliefs. I repeat: God is not bound by our understanding of society, nationality, or religious beliefs.

We think back, of course, to the encounter Jesus had with Nicodemus in the Gospel of John (chapter 3), when Jesus told him: The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.’

God will use whom God will use to bring about the work God wants to do in the world. Our call, our challenge, is to align ourselves with God’s movement and participate with it. This is why spiritual practices are so essential.

Our struggle, if we can be so bold, is that we as the church have inherited a particular image of our own identity that has been caught up and burdened by what we describe, in spiritual and faith development terms, as a mythic-membership mentality. We function in this mythic-membership way of thinking rather than live within the dynamic presence of God as St. Paul describes, in whom we live and move and have our being (Acts 17).

In such a mythic-membership framework, we limit our focus to how we feel we belong in this or that group–this religious tradition, this church, this denomination, etc. And we see our belonging in such a group as meaning that we are “right” about our particular beliefs or thoughts. Everyone outside our group is, therefore, “wrong,” and since our frame of reference is on spiritual truths, so to speak, we begin to feel our rightness has a divine mandate–or our rightness prescribes the only way to interpret reality or God’s movement in the world. Therefore, everyone outside our particular group lacks that mandate, or cannot claim that clarity around divine action, therefore they are outside of grace, outside of blessing, even damned.

Within a mythic-membership framework, if someone thinks differently than we do about God, or if they pray in a different way, they are suspect at best or damned at worst. We simply ignore the fact that Jesus spent so much of his time crossing social and religious boundaries to heal people, never asking anything from them in return.

The ongoing struggle with the institutional aspect of religion, if you will, is that we begin to think our proximity in praising God means that we control or have captured a monopoly on–or have exhausted–God’s movement in this world. Since we are close enough, as it were, to praise God, we begin to think our definition or understanding of God has somehow captured all that God is.

Nothing could be farther from the truth, and we have today’s text to shock us into a wider perspective on God’s action in the world:

Thus says the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus,

whose right hand I have grasped.

I call you by your name, I surname you, though you do not know me.

I am the Lord, and there is no other;

besides me there is no god.

I arm you, though you do not know me,

So we find ourselves here today, in a world riven by conflict, with people of different faith practices and even denominations within Christianity–such as with the Russian and Ukrainian peoples–in all out war. And we struggle to know how to stay grounded, how to respond.

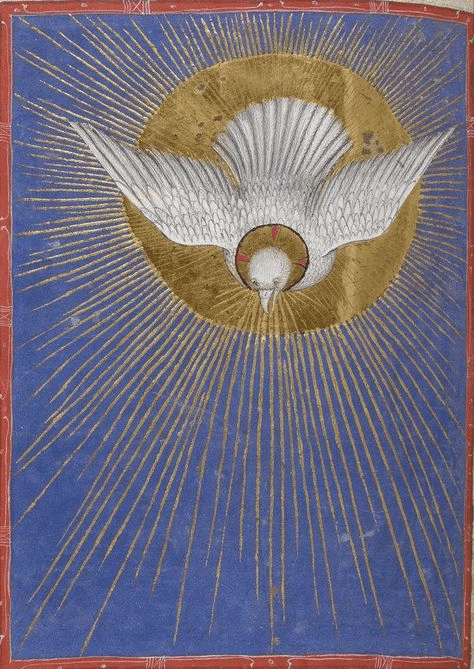

Today, all I have is a prayer that my heart keeps returning to, the Veni Creator Spiritus, Come, Holy Spirit. It is a chant that the church has found meaningful for at least 1,100 years. Perhaps today we can chant this together, on page 504 in your hymnal.

Leave a comment